It is common in youth baseball to play both Spring and Winter baseball. Learn how this could be contributing to the rise of youth baseball injuries and our recommendations for preventing injuries.

Jump to:

For more tips for youth athletes, check out our posts on Omega-3 Supplements for Teen Athletes and Preventing Muscle Cramps.

Major League vs. Youth

With Major League Baseball wrapping up the regular season and transitioning to the playoffs, some players will be entering the off-season while others will be contending for division, league, or world championships. A season that kicked off in late March will be coming to a close seven months later as a World Series champion is crowned in late October. In absence of extenuating circumstances (such as injury), most, if not all, of these players will use their off-season to rest and prepare for next season.

The length, intensity, and volume of a professional baseball season is massive. However, there is a rhythm to the year allowing players to perform at their highest level. During the season all players must pay attention to proper nutrition, adequate sleep, and physical conditioning. For pitchers, this also means rest days and closely monitoring pitch counts. Despite evolving trends in starting pitcher utilization and the role of the bullpen, league leaders continue to post in excess of 200 innings pitched. For those who make it through the year without significant setbacks, professional pitchers use the off-season to rest and recover.

At the youth developmental level, many young athletes, pitchers included, continue to play in Winter Leagues. Professional experience and scientific research suggest that this is to the detriment of those involved.

Why This Matters

My own childhood was filled with sports including baseball, football, and basketball. Growing up in Wisconsin, the seasons were the primary drivers of athletic participation, but I enjoyed all the sports I played and had many friends who did the same. I loved training, practicing, and playing, and I’m thankful that an opportunity arose for me to pursue college baseball.

After my junior season, I was selected in the First-Year Player draft by the Houston Astros. I played parts of 3 seasons at various minor league affiliates and was able to play with or against many current Major Leaguers. Since voluntarily retiring to go back to school and pursue a career as a physical therapist, much of my personal interest remains in athletics and sports performance.

As an aspiring healthcare professional, it is also necessary to think about the long-term well-being of the individuals I will treat. Among my professional goals is to educate parents, athletes, and coaches on current best evidence to decrease injury risk in overhead throwing athletes, to start conversations about youth sport participation that are in the long-term best interests of the athletes, and give suggestions that may help improve athletic development.

The Current State of Youth Baseball

To get a better idea of what’s going on locally, I reached out to a coach in the area who said, “Our current seasons run from September to early December and then February through June. This essentially creates an 8 ½ month season. This is a pretty normal protocol for youth teams.”

Players will want to train and prepare for that 8 ½ months of competition, so it’s becoming more common for kids to be practicing much of the remainder of the year to the exclusion of playing other sports, resting, or dedicating themselves to appropriately prescribed strength and conditioning.

This type of sport participation is currently not supported by some scientific evidence. The authors of one study1 concluded that “early sport specialization does not lead to a competitive advantage over athletes who participate in multiple sports. . . and may put the young athlete at risk for overuse injuries.”

Recommendations for Injury Prevention

Along with the growing popularity of sports specialization, there has been an increase in shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball players. The American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI) released a 2013 position statement that identified overuse, poor mechanics, and poor physical fitness, in order, as the principle factors for this trend. They gave nine recommendations for preventing injuries in adolescent baseball pitchers2:

- Watch and respond to signs of fatigue. If an adolescent pitcher complains of fatigue or looks fatigued, let him rest from pitching and other throwing.

- No overhead throwing of any kind for at least 2-3 months per year (4 months is preferred). No competitive baseball pitching for at least 4 months per year.

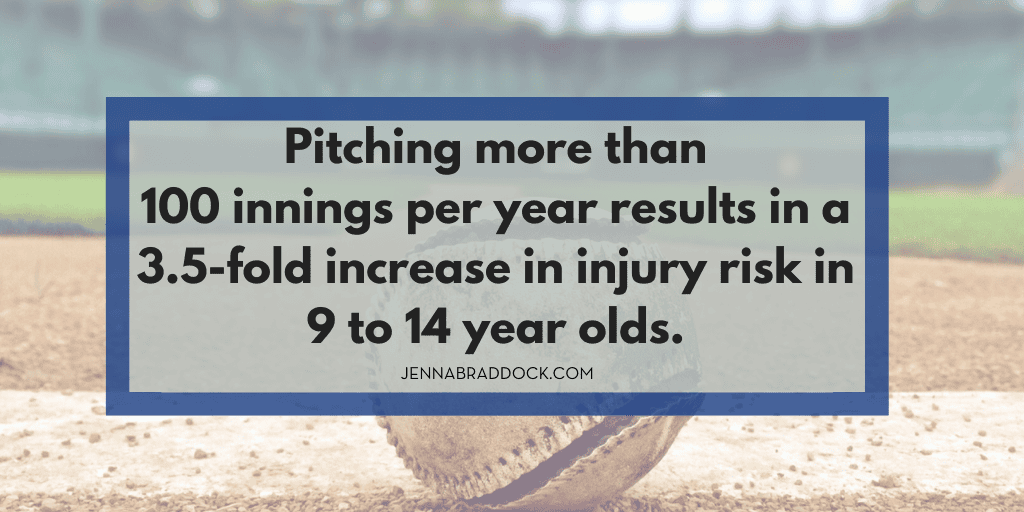

- Do not pitch more than 100 innings in games in any calendar year.

- Follow limits for pitch counts and days rest.

- Avoid pitching on multiple teams with overlapping seasons.

- Learn good throwing mechanics as soon as possible. The first steps should be to learn, in order: 1) basic throwing, 2) fastball pitching, 3) change-up pitching.

- Avoid using radar guns.

- A pitcher should not also be a catcher for his team. The pitcher-catcher combination results in many throws and may increase the risk of injury.

- If a pitcher complains of pain in his elbow or shoulder, discontinue pitching until evaluated by a sports medicine physician. Inspire adolescent pitchers to have fun playing baseball and other sports. Participation and enjoyment of various physical activities will increase the player’s athleticism and interest in sports.

Researchers have identified that pitching more than 100 innings per year results in a 3.5-fold increase in injury risk in 9- to 14-year-olds. These same scientists stated that overuse injuries in youth sport are related to the repeated use of physically immature structures. In addition to other physiologic developmental differences, youth pitchers rely more on trunk rotation and the muscles of the rotator cuff than adult pitchers.1

Parents & Coaches, Listen Up

Unfortunately, parents are not getting this message. A survey found that over 80% of parents had no knowledge of weekly, yearly, or multi-league sport volume recommendations, only 34% indicated concern about the injury risk, and only 43.3% thought that year-round sport participation increased the chances of sustaining an overuse injury.3 Surprisingly few baseball coaches (31%), players (28%) and parents (25%) believe that pitch count is a risk factor for elbow injury.

A similar percentage of baseball coaches, players, and parents do not believe that pitch type is related to elbow injury. Furthermore, 30% of baseball coaches, 37% of parents, 51% of high school athletes, and 26% of collegiate athletes believe that ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction should be performed on athletes without elbow injury to improve performance.1 This lack of awareness and education between parents, athletes, and coaches clearly underlies the rates of injury seen among young athletes.

The Case Against Sport Specialization

There is also evidence for an increased coach-driven emphasis on high-level accomplishment in single sports. Discussing the emotional and psychological components to sport specialization, this area coach said, “some kids also become burnt out at an early age as the pressure from parents and coaches can rob them of the joy of playing the game.” Plus, researchers have hypothesized that these may be some of the earliest instances where the interests and goals of the coach are different than those of the parent and child.1

This same concept came across in my communication with the coach. He said, “Youth sports is a billion dollar industry and coaches will continue to push the envelope and try to convince parents that their son needs to be playing on their team and playing more and more if they want to get better.” I shared the ASMI recommendations with this coach and what he shared with me pointed to the complexity that coaches face. When considering implementing these guidelines, he said, “A coach that is attempting to implement best practices in regards to protecting players arm usage can struggle to field a team if parents feel that their son is being left behind while all the other kids are playing games year round.”

A Challenging Baseball-Balancing Act

There appears to be significant factors relating to present achievement, future ambitions, lack of education, pressure to perform, pressure to offer year-round training, and economic incentives within the player-parent-coach triangle and youth baseball culture that all combine to the elbow and shoulder injury epidemic in youth baseball players. This keeps athletes from appropriately resting, playing other sports, or engaging in a well-designed off-season athletic development program in order to develop the strength and muscular control that is needed to prevent injury and allows for rest from repetitive use of the same muscles and joints.4,5

It’s time for a Culture Change

So, where does this leave us and what can we do? Healthcare providers, parents, and coaches must change the current culture by advocating for a long-term multifaceted institutional and educational approach for these youth athletes that is motivated by what’s in the athlete’s best interest and long-term development.

Overhead throwing is a repetitive and physiologically stressful movement, especially for physically immature players. The increase in shoulder and elbow injuries is evident.2 Collectively, it’s on all of us to educate ourselves on the current guidelines for injury reduction and athletic development and share it with those involved in amateur baseball.

I believe there needs to be regular conversations and shared decision-making between parents and coaches about what is being done not only to promote skill acquisition but also protect these young men’s (or women’s) arms to decrease youth baseball injuries. With this information, we can communicate with these athletes and make well-informed decisions regarding annual sports participation and training patterns that will begin to change the current narrative. It’s time to put the baseball down, enjoy other sports, and get after it in the gym. The best scientific evidence we have to date tells us that your arm will thank you for it.

Author

Daniel Gulbransen, SPT, University of North Florida DPT Class of 2019

Special thanks to Dr. Sherry Pinkstaff, PhD, PT, DPT, for her review and guidance in the writing process.

References

- Feeley BT, Agel J, Laprade RF. When Is It Too Early for Single Sport Specialization? Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(1):234-241. doi:10.1177/0363546515576899.

- American Sports Medicine Institute. Position Statement for Adolescent Baseball Pitchers. http://www.asmi.org/research.php?page=research§ion=positionStatement. Published 2013.

- Bell DR, Post EG, Trigsted SM, Schaefer DA, McGuine TA, Brooks MA. Parents’ Awareness and Perceptions of Sport Specialization and Injury Prevention Recommendations. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;00(00):1-5. doi:10.1097/JSM.0000000000000648.

- Myer GD, Jayanthi N, Difiori JP, et al. Sport Specialization, Part I: Does Early Sports Specialization Increase Negative Outcomes and Reduce the Opportunity for Success in Young Athletes? Sports Health. 2015;7(5):437-442. doi:10.1177/1941738115598747.

- Myer GD, Jayanthi N, DiFiori JP, et al. Sports Specialization, Part II: Alternative Solutions to Early Sport Specialization in Youth Athletes. Sports Health. 2016;8(1):65-73. doi:10.1177/1941738115614811.