Iron deficiency anemia is a real concern for many young athletes, but it can be tricky to identify at first. Here is the story of how a female pole vaulter came to recognize the signs and symptoms of iron deficiency anemia and how she recovered from it. Knowing this information can help prevent your teen athlete from missing play due this common health issue.

For more nutrition tips for teen athletes, check out Meal Planning for Teen Athletes.

Of my many memories of my four years as a collegiate pole vaulter, I will never forget the day during my freshman year that I passed out on the football field during a sprint workout. The experience is still very real to me- the taste of the rubber turf, the horrible abdominal cramps, the shame of walking back to the athletic training room, workout incomplete. At the time, the athletic trainers and I had attributed this incident to not being hydrated or conditioned enough.

To ensure that it would never happen again I did what any ambitious athlete would do: I trained harder.

Intent on not repeating the experience on the turf that year prior, I had practiced some of the harder workouts over the summer and started to grow accustomed to the uncomfortable cramping feeling that seemed to show up at the end of any intense running workout. I felt as prepared as any athlete could be for fall conditioning (i.e kind of, but not really) until our coach told us we’d be doubling up practices in order to cut down the time spent on getting back into shape. One week into conditioning, the cramping started getting worse, and I began feeling out of breath quicker than I normally would. One workout which consisted of ‘ladder’ style sprints up a 400m hill, left me so exhausted that I went home after practice at 5pm and slept until the next morning.

My performance the rest of that week declined quickly. By the end of the week, I remember barely being able to run the warm up lap without feeling fatigued. In a circuit training workout, I had gotten so light-headed and fatigued during sit ups that my eyes were rolling back in my head every time I sat back up. The cramping was getting worse with each work out. At this point, my teammates were also concerned. They noticed the change in my performance – from top three to last.

I was also now sleeping any chance I got. While I was upset about my performance at practice, the need to sleep allowed me to not focus on it.

I went to the athletic trainer, desperate to rid myself of the nauseating/cramping feeling. We talked about making sure I was getting enough sleep and the proper nutrition. He explained that cramping was commonly due to electrolyte imbalance, so he recommended hydrating with only Gatorade before practice. He also recommended changing the timing of my meals.

In the following days neither seemed to help. I made it to the weekend, extremely frustrated and exhausted. My next method of attack would be my mentality. I would maintain a positive attitude no matter how terrible I felt, however; my optimism didn’t last long. Not making a single time during the next workout earned me an extra set of sprints. I didn’t even bother setting my watch because I knew there was no way I would be making the times.

Wanting to Quit

I was on the verge of quitting. I had tried adjusting my water intake, my food intake, maxing out electrolytes, prioritizing 8 hours of sleep, and even adjusting my mentality but I was still exhausted and performing poorly.

Three weeks into fall conditioning, my coach began to suspect something more severe was going on. I received the following text: “Go to the nearest clinic and ask to get your iron ferritin level tested.” Desperate for an answer I scheduled an appointment for first thing the next day. At the clinic I explained to the physician my constant fatigue, lightheadedness, and abdominal cramping with exercise. I was walking to my coach’s office later that afternoon when I received a call back from the physician herself with my lab results:

Iron Ferritin: <5 ug/l

Hemoglobin: 8.5 mg/l

What is Iron Deficiency Anemia

Iron is a micronutrient that plays an integral role in physiologic functions such as oxygen transport and energy production (Alaunyte, 2015). Due to the combination of menstruation, increased iron loss through hemolysis (red blood cell rupture), and insufficient dietary iron intake female athletes are frequently affected by this condition (McClung, 2014).

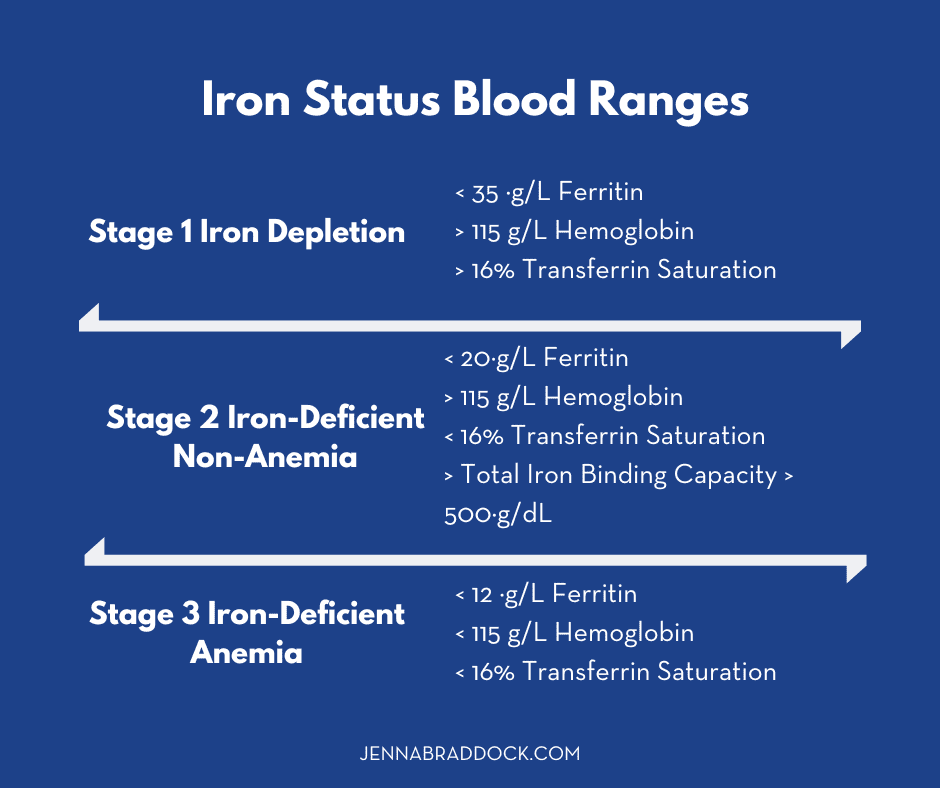

The World Health Organization, and other sport organizations like the US Olympic Committee, use serum (blood) iron ferritin and hemoglobin levels to diagnose iron deficiency anemia. There are 3 stages of iron depletion:

Source: Kapinski, 2017

Signs & Symptoms of Iron Deficiency Anemia

The tricky part of identify this condition is that iron deficiency is asymptomatic in the first stage. As iron levels begin to drop, however, more symptoms arise due to impaired oxygen transport.

Stage 3 indicates that the body’s iron stores have been so depleted that it is no longer able to make new red blood cells, resulting in a decreased ability to transport oxygen throughout the body during rest – let alone during exercising when your body needs even more oxygen.

Other common symptoms of IDA are:

- gastrointestinal cramping

- extreme fatigue

- dizziness

- depressed thyroid function

- decreased ability to regulate body temperature (Suedekum, 2005)

According to the National Institute of Health’s Office for Dietary Supplements, premenopausal female endurance athletes are at a high risk for IDA, especially those that have a restricted energy intake and heavy menstrual bleeding.

Recovering from Iron Deficiency Anemia

Since there are 3 different levels of iron deficiency, each athlete should consult a medical doctor and registered dietitian to determine the best course of treatment. In most cases, an iron supplement is prescribed. Iron supplements are easy to acquire over the counter but still use under the supervision of a medical doctor.

In addition to iron supplementation, rest from training may be required as well as additional dietary changes.

Due to the severity of my low iron level, I was prescribed an iron supplement and was instructed to stop all running for a minimum of 6 weeks to let my fragile red blood cell count increase. I was also advised to take oral iron supplements with orange juice and avoid drinking tea or coffee with meals. This curious combination stems from the ability of vitamin C to enhance iron absorption. Foods such as fruits, potatoes, and leafy greens have high levels of vitamin C which helps the body take in and store the iron we eat in our foods (WHO, 2001).

Calcium

Conversely, the calcium found in milk products, as well as foods that contain tannins such as tea, coffee, cocoa and certain spices largely inhibit the body’s ability to absorb iron. In addition to the high volume of endurance workouts, I had also been drinking iced tea or chocolate milk with almost every meal, thus inhibiting my body from absorbing what little iron I was ingesting.

After six weeks of no impact running, and avoiding tea or milk consumption during meals, I had my blood levels tested again. My hemoglobin level had risen to 9.1 mg/l, and my iron ferritin was at 50 ug/L. I was told to take two more weeks off to let my hemoglobin rise further, and then was cleared to return to practice. As nervous as I was to run again, I had begun to feel exponentially better. My daily naps were no longer needed, and the weight training and cross training (biking/elliptical) no longer left me winded. My first practice back was a hill workout- I would never miss time on a workout for the rest of my collegiate career.

Educate Yourself

At the end of my anemia journey I was happy to finally have an explanation for the suffering I had gone through, but I couldn’t help but be angry and disappointed that I had not been educated earlier on the importance of iron. I learned then that this was in part due to the fact that not all athletes are treated the same. While it is common for track athletes (sprinters and distance runners) to be educated on these issues, it is rare that field athletes (jumpers, pole vaulters, throwers) received the same education.

Impacts

Iron deficiency anemia can have dramatic impacts on an athlete’s physical, emotional and mental health, and yet it is very easy to prevent, or at least catch very early. Education on the importance of a healthy, iron rich diet, especially among ALL female athletes is integral in preventing future cases of IDA and other common sport related issues such as the female athlete triad (a dangerous trio stemming from over-training, inadequate energy intake, and dysmenorrhea, or cessation of the menstrual cycle).

My mental health and self-esteem had also been greatly affected by this event. Had my coach not identified iron deficiency as a potential issue, I’m not sure I would have continued to participate in track and field. I had felt inadequate as an athlete, and my exhaustion often left me hopeless and upset.

Following my recovery, I gained a new outlook on sport performance and perseverance. Although we are often encouraged to push through the pain to get faster and stronger, pushing through my circumstances had left me in worse shape. Once my iron levels had returned to normal, my performance improved drastically and I was safely able to explore my mental and physical boundaries.

Proper iron intake should be priority for all coaches and sport medicine personnel- a simple educational session could be the difference between high level performance and running slow.

Written By

Written by guest coach: Skylar Schoen is a 2nd year student in the Doctorate of Physical Therapy Program at University of North Florida. Originally from Batavia, IL, Skylar attended Grand Valley State University (Allendale, MI) and graduated in 2017 with a degree in Clinical Exercise Science, Pre-Physical Therapy Emphasis. While at GVSU, Skylar competed for Grand Valley’s Track and Field team as a DII collegiate Pole Vaulter. During her time as a collegiate athlete she made three appearances at the Division II National Track and Field Meets (Indoor & Outdoor). Skylar moved to Jacksonville in 2017 and currently is an avid reader, surfer, yogi, and triathlete in training.

I’d like to thank my professor, Dr. Sherry Pinkstaff, and Jenna Braddock for allowing me this space and platform to share my experience with the sports world. I hope that this article encourages both athletes and coaches alike to consider iron deficiency and the importance of identification and prevention in helping promote the highest level of sport performance.

References

Iron Deficiency Anemia: Assessment, Prevention, and Control. World Health Organization. 2001

McClung JP, Gaffney-Stomberg E, Lee JJ. Female athletes: a population at risk of vitamin and mineral deficiencies affecting health and performance. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2014;28:388–92.

Office of Dietary Supplements: National Institutes of Health. Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Iron. Accessed at: http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iron-HealthProfessional/

Suedekum NA, Dimeff RJ. Iron and the athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2005;4:199–202

World Health Organisation. Assessing the iron status of populations. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2007

Whiting SJ, Barabash WA. Dietary reference intakes for the micronutrients: considerations for physical activity. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006;31:80–5

Alaunyte et al. Iron and the female athlete: a review of dietary treatment methods for improving iron status and exercise performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (2015) 12:38

Karpinski C, Rosenbloom C. Sports Nutrition: A Handbook for Professionals, 6th Edition. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2017.