Intermittent Fasting has become a very trendy strategy for a variety of desired outcomes from weight loss to longevity. Just like with the Keto diet, it has important benefits but is also easily misunderstood and misapplied. I’m sure you have heard many fasting success stories from personal friends or people on the internet. While these are great, it doesn’t necessarily mean that this is a rock-solid, science based strategy, yet.

Jump to:

This post had taken me a couple of months to write as there was a lot of research to review, each article unlocking more questions that needed answers. I still don't feel like I'm done, but as some point, you have to hit publish. I will be continuing to update this post as I come across new research. This is me trying to do my due diligence to turn over as many rocks as I could about the mysteries of intermittent fasting. This post is a loooonnnggg one, so get comfortable and try to hang on till the end.

As I did with my keto diet post, I will try to keep this as neutral a tone as possible. I’ll conclude with my opinion, should you want it. In general, this post will explain intermittent fasting, describe the science available in as easy to understand terms as possible, and how to implement it, if it’s right for you.

To see the references used for writing this synopsis, click here to access the google drive of all the full articles. I didn't do the best job of referencing directly in this post, and I do apologize. As I continue to review and update, I will add in the specific references.

What is Intermittent Fasting?

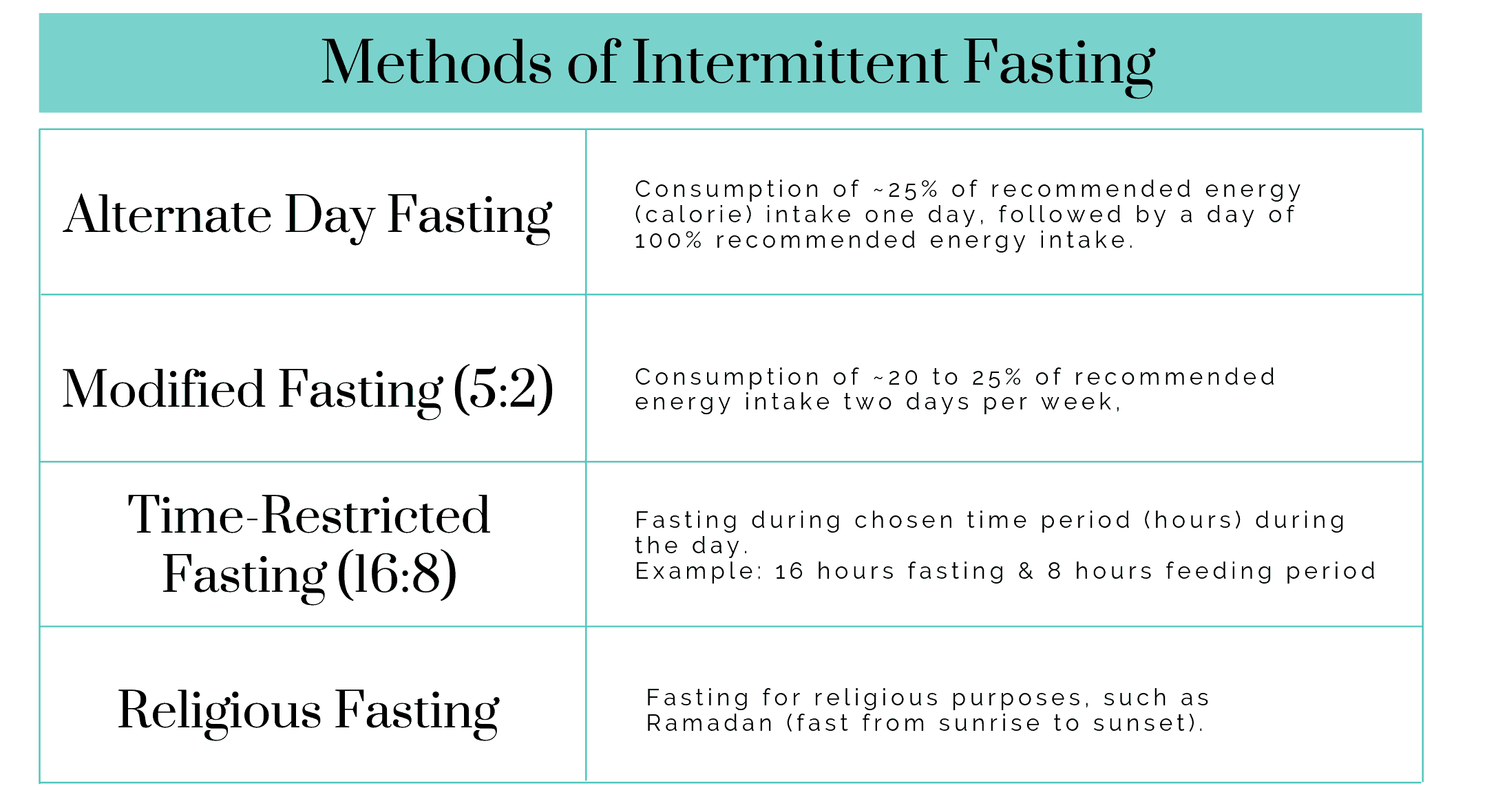

Intermittent fasting (IF) is defined as a period of time where for multiple hours or days you fast, or abstain from food and/or drink which is then followed by a time period of unregulated (“normal”) eating. Though it is ultimately considered a form of calorie restriction, there are multiple eating patterns including alternate day fasting, modified fasting (also considered 5:2), time-restricted feeding (16 hour fasting:8 hours eating in a 24 hour period), periodic fasting, and religious fasting. In a nutshell, it’s alternating between time related calorie restriction and normal eating. This differs from traditional consistent calorie restriction, which limited calories daily as a way to promote weight loss.

A period of fasting could consist of total abstinence from food or drink (other than water) for a total 24 hours, followed by a day(s) of regular eating. It could also look like fasting from food and drinks (other than water) for a set number of hours during a 24 hour time period (like 12-18 hours), followed by a shortened time window of regular eating.

There is no “standard” (or scientifically sound) protocol for intermittent fasting at this time. A lot of research was reviewed for this post and they almost all used a different fasting definition. Most commonly, a day of fasting consisted of reducing daily food intake anywhere from 20-45% of total energy (calorie) needs. Because of these study design differences, it’s tricky to compare research studies for larger population application.

What seems to be the most studied protocol of IF is either 2 consecutive days of calorie restriction followed by 5 days of normal eating or alternative days of time related calorie restriction with normal eating. (Harvie, 2017) As I discuss the different outcomes of IF throughout this article, understand that I am referring to all protocols collectively, and not one in particular, because each study is different. I know that stinks, but that’s the way it is right now.

In 2019 I was interviewed on Intermittent Fasting. Check out the interview below:

How is IF different than typical calorie restriction?

Traditional calorie restricted diets, defined as a long-term daily reduction of 20 to 40% of recommended total daily caloric needs without malnutrition, have been studied for decades and have strong evidence for promoting health and longevity. The problem lies in the fact that very few people want to live on a restricted calorie diet, and for many, it won’t sustain their needed level of activity. There’s a lot more that could be unpacked here but I’ll leave it short and sweet to get on with our bigger point.

IF has come on the scene as a potential alternative to long-term low calorie diets as it’s more flexible by allowing oscillating between food restriction and normal eating. Much of the research is finding that the benefits seem similar between the two approaches, with IF offering a more realistic approach. IF has also been found to produce similar benefits to the ketogenic diet, another hard diet style to follow but with noticeable benefits. You can get all your questions answered about the Keto Diet in this post.

There also seems to be some “secret sauce” to the length of time one goes without food during periods of IF. While I am having difficulty finding original research to actually support this, it is commonly discussed in scholarly work that abstaining from food for 12-18 hours produces profound cellular and metabolic benefits that are only initiated in times of fasting. These benefits can be turned on through intermittent fasting periods and not just through a continuous very low calorie diet or long-term fasting, as was once thought.

The research on IF is clearly showing a benefit on total health. The biggest challenge to answering the question “is IF an important thing I should do for better health?” is that the research we have available is not conclusive in giving an answer. Studies are designed differently with different fasting protocols, use animals or humans, have multiple factors that could have produced results (or lack thereof), and have conflicting results. Therefore, at this time, it’s impossible for me to recommend this as a global strategy for better health. However, there are some promising results from research that give me hope that this could be something significant to pay attention to.

Here’s the breakdown on what we know so far.

What are the potential benefits?

There are a lot of proposed benefits to intermittent fasting floating around on the internet. Here’s what the research says on the major areas of potential benefit.

Impact on Weight

Studies have shown that IF leads to weight loss in overweight and obese participants, specifically with alternating one day of “fasting”, defined as consuming 25% of recommended daily energy, followed by a day of recommended caloric consumption. It is important to note that most studies persuaded or counseled participants on not overeating and following a balanced diet, such as the Mediterranean Diet, on fed days. These suggests that what you eat on normal days of eating does matter and could have an impact on long term weight loss efforts and overall health.

A review of studies has looked at weight maintenance after loosing using IF and found that IF is equivalent to daily calorie restriction in weight loss effectiveness and potentially superior for promoting fat loss, although there was just one study that showed this. (Harvie, 2017)

Unfortunately, research has not investigated IF as a long-term method for preventing weight gain in normal weight humans. Until research is conducted, it is speculative, at best, to say IF can help prevent unwanted weight gain.

Fat Loss & Body Composition

Fat loss is often described as a major benefit of IF. Similar to the Keto diet, in the absence of glucose from food for energy, the body uses stored fat for energy more readily and easily. Animal studies have looked at this from an application view point, as in, we know that should happen, but does it really? The results are rather interesting in what happened with rats:

- Alternating fast days led to no change in weight or body fat, but fat was positively redistributed in the body.

- Alternating fast days did not impact abdominal fat.

- Alternating fast days (of 50% calorie restriction) reduce fat cell size of both abdominal fat (by 35%) and fat under the skin (by 50%). (Harvie, 2017)

- IF reduced weight but increased body fat and negatively impacted insulin sensitivity. Some of this response is thought to possibly be related to binge eating the rats engaged in after periods of fasting.

Hopefully this shows you just how hard it is to draw conclusions from research, much less intermittent fasting research.

Research on humans and body composition changes induced by IF are also not very clear.

Shocker!

It does look like IF somewhat consistently promotes a loss of liver and abdominal fat. Fasting of any type will trigger your body to breakdown fat and put it into your bloodstream so it can travel to different cells and be utilized for energy. In general, this is a good thing if you have an amount of body fat that is potentially detrimental to your health and well-being.

One of the questions that still needs an answer here though is if promoting this flood of fat (more specifically fatty acids) to your bloodstream on a semi-regular basis or rhythm is always a good thing. For instance, for someone with metabolic syndrome, who already has high triglycerides (a type of fat) in their blood, is it good to add more fats, even momentarily, to their blood. Metabolism is NOT a straightforward situation, so for me, this question needs an answer, especially as I practice Medical Nutrition Therapy with clients.

Another potential benefit of IF is that it could help preserve lean body tissue (most specifically muscle) while losing body fat, which is ideal and good. However, some results show that it’s really no different than regular calorie restriction in promoting both fat and unintended lean body tissue loss. The most important factor to combat the loss of muscle is to add in exercise, specifically resistance exercises. (Harvie, 2017) See more about this specifically below.

There also seems to be differences in how males and females respond to IF in regards to loss of body fat, and even more specifically, pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women. I personally think this suggests that research may eventually show us unique protocols for men and women in their various stages of life.

Diabetes

Research suggests that IF may be a feasible option for those with type 2 diabetes to help improve insulin resistance. Studies show that IF improves insulin sensitivity in participants who also lost weight. In a study that compared 2 consecutive days of fasting (restricting calorie intake by 70% on 2 of 7 days) a week to every daily calorie restriction, the 2 day a week fasting group had significantly greater improvements in insulin sensitivity, even though both groups experienced comparable weight loss. That’s saying something.

This doesn’t negate the fact that positive lifestyle modifications of any kind, such as an increase in physical activity and improved dietary choices, is beneficial in decreasing fasting glucose and improving glucose tolerance. It just may mean that incorporating a couple of days of intermittent fasting in a week may lead to greater improvements.

Regardless, it’s very important to say that before trying ANY new eating approach, people living with type 1 or 2 diabetes must consult with their physician and/or Certified Diabetes Educator (CDE, usually a RN or RDN). IF is a pretty significant lifestyle change and can impact medication and insulin needs. Do not try it without the consent and help of your health care providers.

Sleep

Though some individuals may not experience a lack of energy during the day, studies have shown IF may disrupt sleep and decrease durations of REM sleep, or deep sleep.

Cancer

There is very limited conclusive research regarding cancer prevention and IF. IF may reduce risk of cancer related to its beneficial effect on preventing oxidative stress, inflammation, and cellular damage. One study concluded IF may be beneficial for cancer prevention due to the process of the body using ketone bodies in place of glucose through the process of ketogenesis. This is significant because cancer cells seem to only be fueled by glucose. Therefore, in theory, if glucose is not available, cancer cells do not have fuel to continue to replicate.

Mental & Brain Health

There is conflicting findings about overall mental health effects and IF. It may be more beneficial, in terms of mental health, compared to daily calorie restriction as studies have shown longer compliance with IF. However, during fasting days individuals may experience feelings of increased appetite and irritability related to either energy restriction or disrupted sleep. These feelings may result in becoming “hangry” (hunger & angry) or a decrease in self-control related to food choices during feeding periods.

Some research shows that calorie restriction may be beneficial in delaying the onset or progression of some neuronal dysfunctions such as Alzheimer's, Parkinsons, and Huntington’s disease; however this has not been exclusively studied with IF. One study found that IF impaired cognitive function and decision making, however other studies have shown improvements in memory performance. The verdict is still out on how much IF could impact brain health and mental disease prevention.

Cell Health/Mitochondria

Perhaps some of the most intriguing benefits to IF relates to cell health, specifically in the mitochondria. The mitochondria is considered the powerhouse of the cell and is particularly susceptible to damage through inflammation. IF initiates metabolic processes that protect and clean up the mitochondria and contributes to overall cell vitality. This is in essence, creating good health at your core. It seems that these important systems are only initiated in a fasted state. This, to me, is one of the stronger cases for the importance of IF.

Metabolic Flexibility

This term is new to me but very intriguing. There is an idea in the world of metabolism that it is good for our cells to be able to switch easily between glucose burning (which is what happens after we eat) and fat burning (which is what happens most readily in a period of fasting). It’s thought that this keeps cell working optimally and triggers lots of great, health-promoting processes. It’s a nifty idea and I can sort of see the value in it, but there’s just not the data yet to support that this sort of metabolic exercise is necessary. This doesn’t mean it is not beneficial, it’s just not supported by science yet. (Harvie, 2017)

Gut health

One of the most common reasons I hear in support of IF is to “allow the gut time to fully rest”. This one always perplexed me and I’ve looked for a solid, science based answer to support or deny this claim.

In researching for this article, I came across a great review of IF which does speak to this potential benefit on the gut:

“IF enhances parasympathetic activity (mediated by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine) in the autonomic neurons that innervate the gut, heart, and arteries, resulting in improved gut motility and reduced heart rate and blood pressure.” (Cherif, Roelands, et. all)

This little snippet offers, to me, a practical explanation for why IF may help our gut work better. By “enhancing parasympathetic activity”, IF increases the relaxation of the nervous system and down regulates the stress response of the sympathetic nervous system (fight, flight or freeze). This could, in theory, allow the gut to work better overall and digest more effectively.

Beyond this snapshot though, I wasn’t able to find a deeper reason to why IF may help the gut.

What are the potentials risks?

In general, there are still a lot of unknowns with IF, especially for long term use. While this doesn’t necessarily mean intermittent fasting is unsafe or unhealthy, it should still be scrutinized before implementing. Most researchers conclude their papers with some sort of disclaimer about more needing more research before making a definite recommendation.

One of the biggest “risks” that concerns me is that the results of studies are mixed. To extrapolate this a little further, I think your genetics will play the most significant role in whether IF is helpful or hurtful for you. The only way to know is to try it and see what happens.

Fasting has the potential to mess with your reward center in your brain and make it more difficult to be in tune with your body’s natural cues. One study found that brief episodes of food restriction set people up to desire higher calorie foods. This is likely because more dopamine, the reward neurotransmitter, is released in the brain when you eat after a time of food restriction. More dopamine means a greater desire to keep experiencing this “reward”, which in this case, would be food.

IF has found interesting side effects in normal and overweight people. Limited studies found that participants reported greater hunger on an IF regimen and also had difficulty maintaining normal activity level when fasting. (Harvie, 2017) These outcomes were specific to the protocols used in these studies, which once again makes it difficult to draw universal conclusions. But nonetheless, these findings are noteworthy and should be recognized as potential risks.

Long term fasting that turns into significant calorie restriction can negatively impact energy levels, mental health, and heart health. There’s also potential to impact memory and ability to concentrate. In some cases, it can easily turn into disordered eating with extreme restriction of food. In either of these situations, the risks will outweigh the benefits.

Study results are mixed on the impact of fasting on cognitive (brain) performance. Some research has shown a decline in brain performance while others actually show an improvement in performance and even an increase in new neurons and synaptic plasticity. While there is promise in this area of health (as discussed more above), there is a risk that it might negatively affect your brain power.

Lastly, the long term evidence on IF and sustained weight loss is lacking. Research has not yet shown if IF is a good strategy for preventing weight gain in normal weight humans. Because of this and some of the other risks mentioned above, I don’t think weight loss alone is the reason to implement IF.

Who should not try intermittent fasting?

IF is not a good choice for when your body truly needs fuel to perform at its best, for example when training for a fitness goal, competitive sports, or in the midst of a very demanding schedule. It is also NOT appropriate for pregnant/lactating women, kids, teens, or young adults who are still growing and developing and have higher nutritional needs.

Interestingly, I have noticed that IF seems very popular among young adults (20's in particular). I understand why there's a big draw to it, but based on the research I have seen (there's always more I could read) I do not see the real benefits for this life stage. First, especially for men, growth continues into the 20's. Limiting caloric intake and availability at this time could be a situation where the risks on lifelong development and health outweigh the benefits. Many young adults are in a season of life where they're working hard - in school or in a new job - and they need fuel! Limiting oneself purely for the sake of doing so, could be detrimental to performance and growth. Second, I have a hunch that IF could negatively impact bone development, which continues till the mid 20's. I need to dig into research to see if there's anything there, but I feel like IF could impact both gender's ability to lay down vital bone structure that will impact their health for the rest of their life. Time will tell on that one. Ultimately, for young adults, prioritizing a fasting regiment over your performance in life, overall health, and personal well-being is not wise.

Athletes are another group that I think should mostly avoid IF. There is potential to use IF in a calculated way to enhance desired body changes, but the keyword is CALCULATED. IF should be implemented with the input of a registered dietitian for athletes to truly benefit. Otherwise, I do not suggest athletes who are looking to improve their performance utilize IF in their regular training regimen.

The biggest problem I see with IF, as with any diet that has potential benefits, is when a person takes it too far (and never eats enough food to fuel their body) or becomes so rigid to the fasting rhythm that they sacrifice other important life situations just in the name of fasting. Neither of these is healthy or correct. If you have struggled with disorder eating in the past (i.e. restrictive eating, binge eating, or orthorexia) I do not recommend attempting IF.

What is the best method for IF?

Unfortunately, there is not a good answer for this question. None of the studies I reviewed (and I read a lot) concluded with an IF protocol they recommend. That’s right. No researcher had a good guide for how to implement fasting into lifestyle. The evidence is just not solid, or conclusive enough.

Most of the studies used a specific calorie restriction to dictate the fast, not a window of time. Therefore, any recommended “eating window”, the time you do eat, seen in the IF world (8, 10, or 12 hours) on the internet is someone’s personal conclusions about how they think IF should be implemented. That’s a problem in my opinion but, not necessary a bad problem. Basically, a limited time period does two things: 1) it naturally limits your calorie intake and 2) it helps promote that “secret sauce” effect on metabolic processes that are only initiated with longer periods of time not eating.

It's also important to note that the majority of fasting should be done overnight. This helps utilize a time period when energy demands are low (due to being asleep) and maximizes the body's metabolic pattern to use up all stored energy, waking up in a near fasted state already. Fasting too far into the day can compromise energy, performance, brain power and emotional resilience.

What I think is safe to conclude from the research is that intermittent calorie restriction or fasting of some type can produce benefits to health and vitality. What exactly that should look like though, is cloudy. Keep reading to get my recommendation (aka my interpretation of the science) for how to get started with IF.

How to try intermittent fasting

It’s honestly hard for me, as a Registered Dietitian, to come out and say exactly what I think is a smart and safe way to IF because the research is so vague on this. But, I also want to be helpful to those who want to safely try this approach to see if they do benefit. So I’m going to do my best.

Before beginning any type of IF, it is recommended you consult with a physician and/or registered dietitian to make sure it is safe for you. Also, if you fit into one of the categories mentioned above in “who should not try IF”, this is not the time for you play around with IF, and you may never be a good candidate for it.

The potential benefits of IF are promising enough, to me, to consider implementing it into certain lifestyles. However, I think IF should be done on purpose, not haphazardly. This means you shouldn’t just “happen to not eat till 2pm” and say, “I’m guess I’m fasting today!” What really is going on there is you are not listening to your body. More on that another day.

One of the keys to reaping the greatest benefits from IF is to combine it with exercise. Exercise has incredible power to enhance brain function and it seems to help offset the mental lethargy that reducing calorie intake can have. It also helps build muscle and protect what you already have. This helps you NOT lose muscle during fasting periods. Make sure you are already exercising regularly and are able to support your exercise regimen with the fuel you need to meet specific goals. I do not recommend having a fasting day on the same day as long, demanding, or high intensity workouts. There is potential for the risk to outweigh the benefits. Instead, plan moderate intensity workouts lasting 30-45 minutes, to start, and see how your body responds.

IF is not a replacement for a healthy diet, so what you do eat when not fasting still matters. In fact, a nutrient rich diet supports the body to ensure all the benefits of IF are actually able to happen. A diet high in fruits and vegetables is perhaps the most important, while eating adequate protein, healthy fats and fiber rich foods also matter significantly. In many of the studies on IF, participants were encouraged to eat a diet similar to the Mediterranean diet. So don’t use IF as a license to kill and eat whatever during your eating window.

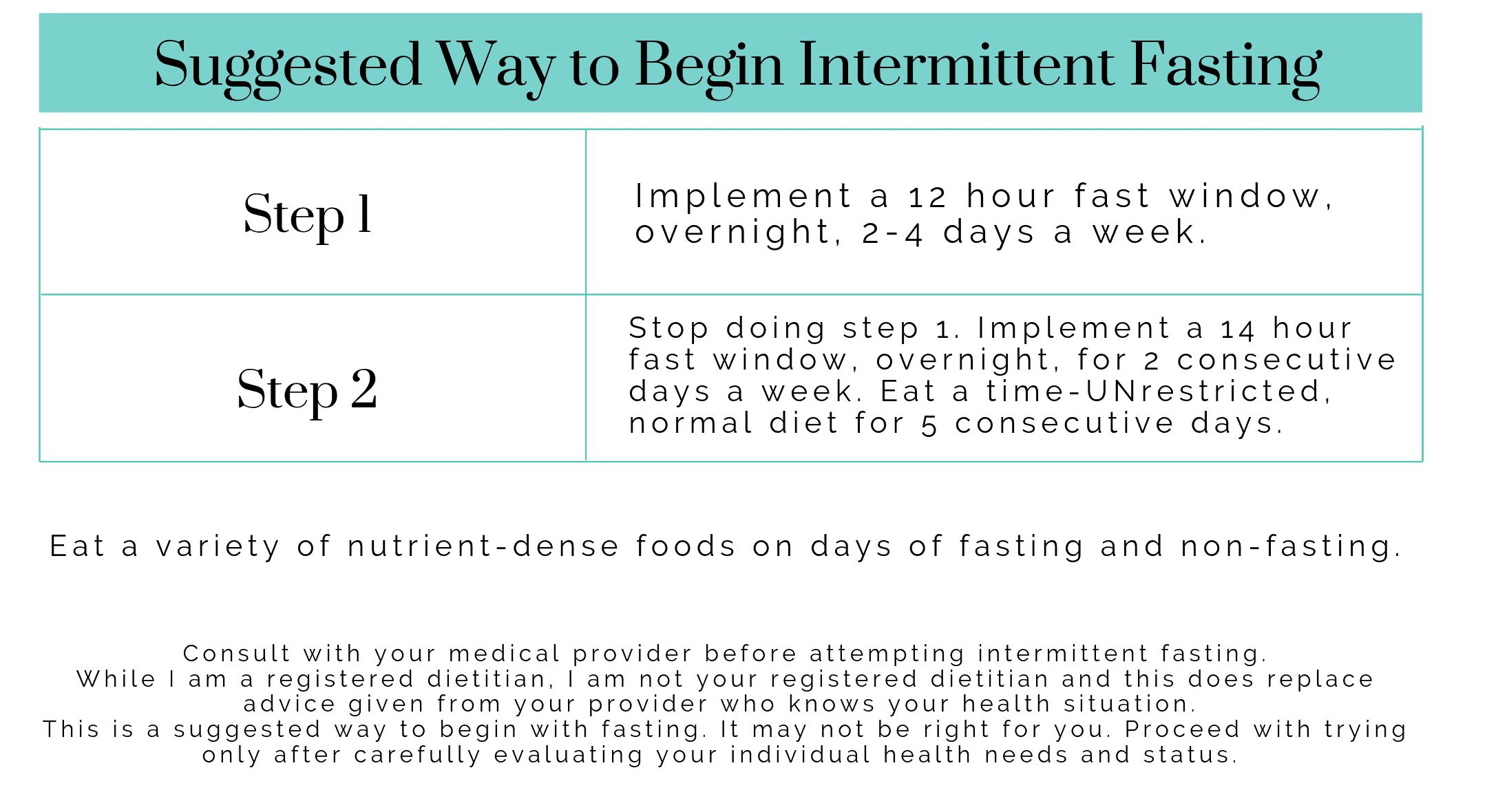

Once you know you are in a place of good health to try experimenting with IF, I would suggest starting with a 12 hour window of eating to fasting. This could be as simple as stopping eating of anything with calories (water is NOT off limits so keep drinking it) from 7pm - 7am, or any variation of 12 hours that works for you. This honestly is not a bad strategy for a lot of people as it helps naturally regulate total food intake. It is not, however, a hard fast rule to never break. If you find yourself truly hungry in the evening, by all means, listen to your true hunger and honor it.

If this seems like the 12 hour window is working for you, you could experiment with increasing the fasting window to 14 hours, like 6pm to 8am, a couple of days a week. Some of the research studies that had good results on humans had 2 consecutive days of limited eating with 5 consecutive days of normal eating. This sounds like a good plan to me to start with. One of the good qualities of IF that I like is that it seems like you do not need to do it everyday to experience cellular health benefits.

To break it down more directly:

Increasing your fasting window to 16 hours, leaving only 8 hours to eat, is not something I am comfortable recommending in this setting of an article because so many variables are in play in your personal life.

If at any time while experimenting with IF you feel that your energy, mental capabilities, mental health, strength, performance, or vitality is impaired, STOP. You gave it a good try, but it just might not be for you. You’re not broken and it’s OK.

If you have made it all the way to end here, I commend you. Thank you for taking the time to read it. I hope it was helpful and easy to understand. If you have questions still, please leave a comment and I will do my best to answer them.

Have a healthy day!

Jenna